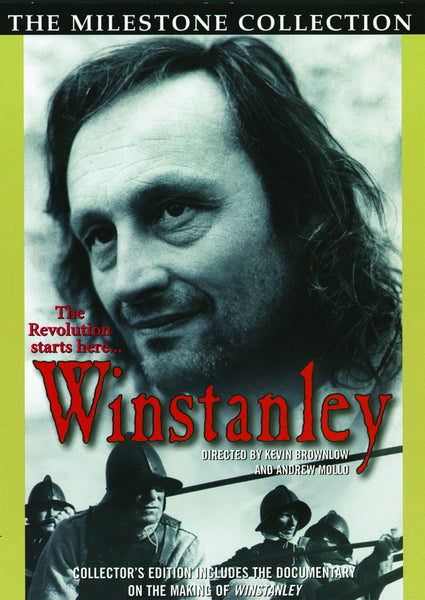

Povijesni film koji zaista izgleda kao povijesni film, u smislu da bi vjerojatno ovako nekako izgledao film iz 17. stoljeća. Pored toga riječ je o utopijskom projektu stvaranja zajednice u kojoj su svi ljudi jednaki.

Jonathan Rosenbaum: "There's really not much to be said for 'Winstanley', except that it's the most mysteriously beautiful English film since the best of Michael Powell (which it resembles in no other respect) and the best pre-twentieth century historical film I can recall since 'The Rise of Louis XIV' (Rossellini) or Straub's 'Bach' film ('The Chronicles of Anna Magdalena Bach')."

1649. With poverty and unrest sweeping England, a group of impoverished men and women, known as the diggers, form a settlement on St George's Hill, Surrey. Inspired by the visionary leadership of Gerrard Winstanley, the commune's tireless, yet peaceful, attempts to assert their right to cultivate and share the wealth of the common land, are met with crushing hostility from local landowners and government troops.

With Winstanley, filmmakers Brownlow and Mollo (the creators of It Happened Here) have produced an astonishingly authentic historical film, and a powerful, moving story of one extraordinary man's vision.

"Brownlow and Mollo’s great movie about a short-lived idealistic commune in Cromwell’s England is the most revealing film about Britain and the 1960s revolution. That neither directed another feature after It Happened Here and Winstanley is one of the major tragedies of British cinema" Philip French (Critic, ‘The Observer’)

"Boasts one of the all-time great cover puff-quotes, from Christopher Hill, doyen of Civil War historians. “This film”, he wrote in Past and Present on its release in 1975, “can tell us more about ordinary people in seventeenth-century England than a score of textbooks." Henry K. Miller (Academic, UK)

The Levellers were a relatively loose alliance of radicals and freethinkers who came to prominence during the period of instability that characterized the English Civil War of 1642 - 1649.

What bound these people together was the general belief that all men were equal; since this was the case, then a government could only have legitimacy if it was elected by the people. The Leveller demands were for a secular republic, abolition of the House of Lords, equality before the law, the right to vote for all, free trade, the abolition of censorship, freedom of speech, the abolition of tithes and tolls, and the absolute right for people to worship whatever religion they chose, or none at all. This program was published as "The Agreement of the People".

The Levellers argued that since God had created all men as equals, the land belonged to all the people as a right. Their program was, then, essentially an attempt to restore the situation that they believed had existed previous to the Norman Conquest in 1099; they wanted to establish a 'commonwealth' in which the common people would be in control of their own destiny without the intervention of a King, a House of Lords and other potential oppressors.

It is hardly surprising, given this program of demands, that the rich and powerful felt threatened by the Levellers. This is particularly so, given that some of the Leveller demands, almost 400 years on, have still not been met!

In 1649 Gerrard Winstanley and fourteen others published a pamphlet in which they called themselves the "True Levellers" to distinguish their more radical ideas from the Levellers. Once they put their ideas into practice and started to cultivate common land, they became known as "Diggers" by both opponents and supporters. The Diggers' beliefs encompassed a worldview that envisioned an ecological interrelationship between humans and nature, acknowledging the inherent connections between people and their surroundings.

Winstanley would advocated a new democratic society of the "common man" as opposed to the current society based on privilege and wealth. Many of the political, economic and social reforms advocated would dramatically impact the social order. Winstanley was concerned by the plight of the people at the lower rungs of English Society, the overlooked or forgotten man. The poor, the sick, the hungry, and the destitute who often did not scrape by or were left to die.

The Digger movement at St George's Hill (Surrey) provided an ideal venue for testing Winstanleys' new social experiment. Winstanley rejected the concept of private ownership of all land, and called for a peaceful return of all public lands to the People. Some have even characterized the Surrey Diggers' as a primitive Millennium movement. Later generations have called the social experiment an early form of communism or even anarchism.

What bound these people together was the general belief that all men were equal; since this was the case, then a government could only have legitimacy if it was elected by the people. The Leveller demands were for a secular republic, abolition of the House of Lords, equality before the law, the right to vote for all, free trade, the abolition of censorship, freedom of speech, the abolition of tithes and tolls, and the absolute right for people to worship whatever religion they chose, or none at all. This program was published as "The Agreement of the People".

The Levellers argued that since God had created all men as equals, the land belonged to all the people as a right. Their program was, then, essentially an attempt to restore the situation that they believed had existed previous to the Norman Conquest in 1099; they wanted to establish a 'commonwealth' in which the common people would be in control of their own destiny without the intervention of a King, a House of Lords and other potential oppressors.

It is hardly surprising, given this program of demands, that the rich and powerful felt threatened by the Levellers. This is particularly so, given that some of the Leveller demands, almost 400 years on, have still not been met!

In 1649 Gerrard Winstanley and fourteen others published a pamphlet in which they called themselves the "True Levellers" to distinguish their more radical ideas from the Levellers. Once they put their ideas into practice and started to cultivate common land, they became known as "Diggers" by both opponents and supporters. The Diggers' beliefs encompassed a worldview that envisioned an ecological interrelationship between humans and nature, acknowledging the inherent connections between people and their surroundings.

Winstanley would advocated a new democratic society of the "common man" as opposed to the current society based on privilege and wealth. Many of the political, economic and social reforms advocated would dramatically impact the social order. Winstanley was concerned by the plight of the people at the lower rungs of English Society, the overlooked or forgotten man. The poor, the sick, the hungry, and the destitute who often did not scrape by or were left to die.

The Digger movement at St George's Hill (Surrey) provided an ideal venue for testing Winstanleys' new social experiment. Winstanley rejected the concept of private ownership of all land, and called for a peaceful return of all public lands to the People. Some have even characterized the Surrey Diggers' as a primitive Millennium movement. Later generations have called the social experiment an early form of communism or even anarchism.

After repeated attacks and destruction of their commune and crops by local landowners (particularly by hired thugs and ill-informed peasants) and fines from the high authorities, the Diggers soon faded away.

But, as with the Levellers, Winstanley and the Surrey Diggers struck a blow at the halls of wealth and power of 17th century English society. Their efforts and their philosophy were not wasted on later generations seeking the same spirit of liberty and freedom in a more democratic social structure.

Kevin Brownlow: a life in the movies

Kevin Brownlow has won a lifetime-achievement Oscar and made superb films. So why isn't he better known?

Philip Horne

A passionate amateur in the best sense ... a still from Kevin Brownlow's 1976 film Winstanley. Courtesy of the British Film Institute

On 13 November last year Kevin Brownlow received an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement, alongside Francis Ford Coppola (Jean-Luc Godard didn't turn up). In his letter of nomination, Martin Scorsese declared that "Mr Brownlow is a giant among film historians and preservationists, known and justifiably respected throughout the world for his multiple achievements: as the author of The Parade's Gone By, a definitive history of the silent era, and . . . a biography of David Lean . . . and as the director with Andrew Mollo of two absolutely unique fiction films, Winstanley (1975) and It Happened Here (1964) . . . On a broader level, you might say that Mr Brownlow is film history." This sums up pretty well the extraordinary record of a remarkable Englishman.

But while Brownlow's achievements – as a historian of film, in preserving and restoring silent-era classics, and as a director in his own right – have commanded respect, he has never played the career-building game. His Oscar acceptance speech began: "If you ever wondered what reflected glory looks like, this is it!" And it went on to remind the Academy of Hollywood's wretched record, destroying 73% of pre-sound films: "By God, your predecessors did a terrible job of preserving the silent era!" Silent films have always been a cause that needed defending, he told me: "The reason I was doing it was because nobody else was."

So far Brownlow has not been conspicuously honoured in Britain; but then, he has always been rousingly undiplomatic about the shortcomings of the British film industry. This wonderfully English figure – a passionate amateur in the best sense, immensely knowledgeable and wry and idealistic – has often been at loggerheads with this country's movie establishment.

Starting as a teenage silent-cinema enthusiast in the 1950s, Brownlow interviewed a dazzling array of film pioneers. He met and became friends with Abel Gance, director of Napoléon (1927); and also (despite his liberal views) with Leni Riefenstahl. Among the royalty of old Hollywood he met (and in many cases became friendly with) Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, Fay Wray, John Ford, King Vidor, Howard Hawks, Frank Capra, David O Selznick and Fritz Lang. He got to watch Charlie Chaplin directing, despite the strict closed set at Pinewood for The Countess from Hong Kong (1967), because he turned up with Gloria Swanson.

At his school in Crowborough, East Sussex, the headmaster showed silent films on a 9.5mm projector. That inspired him to ask his parents for a 9.5mm projector of his own, and he became a passionate collector. He encountered Gance's Napoléon, which was to change his life, in 1954. "It was to me the first glimpse of what I thought the cinema should be, in which everything looked incredibly real, and yet the camera was doing astonishing things that I'd never seen before, or since."

The excitement of this fragmented two-reel version of Gance's five-hour-plus epic led him, while still at school, to seek out other 9.5mm prints of the film. He found one on a stall in Paris. "My first restoration was on Napoléon, trying to put the French version in with the English version, and it was most unsatisfactory." He has been reconstructing the film ever since, as further footage is unearthed in archives. In 2000 his third major restoration premiered at the Royal Festival Hall to 2,200 people – with a full orchestra and Gance's original triple-screen spectacle. Alas, this sublime five-and-a-half-hour version hasn't been shown since 2004.

When he left school he became a trainee in the Soho cutting rooms of World Wide Pictures. In the business, he heard much talk of the Al Parker actors' agency, and connected it with the actor Albert Parker, villain of Douglas Fairbanks's American Aristocracy (1916). "I rang him up, and said: 'Does the name Fairbanks mean anything to you?' He said: 'Jesus Christ! Doug? I directed him!' And I said: 'What in?' And he said: 'The Black Pirate!' I said: 'I think I've got one of your very early films.' He says: 'Bring it over.' So I took my little hand-cranked projector and I showed it to him on the wall – and he got absolutely fascinated."

While working as an editor he doggedly pursued the surviving silent movie pioneers for interviews, which eventually became the substance of The Parade's Gone By (1968). Two more major studies of silent film followed: The War, the West and the Wilderness (1979) and Behind the Mask of Innocence (1990). He went to the US for the first time in 1964: "To be honest with you, I was chasing a girl. She was an actress who had gone back to New York. So I needed an excuse." While she rehearsed he tracked down silent-film veterans. He flew on to Hollywood and managed to pack in multiple interviews. Josef von Sternberg, he says, was "very, very difficult", even though "I was mad about his silents". Later he met Sternberg's great star, Marlene Dietrich – a contrast to her mentor. "What really amazed me was how warm she was. She pretended she wasn't in silent pictures because it dated her."

Brownlow had made an early start in journalism too, and, even more precociously, by 17 he'd made a first film, The Capture (which doesn't survive), based on Maupassant. In 1956, inspired by hearing a German shout in the streets of Soho, he began making the extraordinary It Happened Here, about a putative German occupation of England in 1940 – starting, cheekily, with a Nazi rally in Trafalgar Square. As it developed, with the help of Mollo as co-director, the film became a corrective to the myths of English wartime exceptionalism: "If the Nazis had come over it would have been just like France and the Netherlands and everywhere else." The finished film, with its painfully believable dark vision, was a succès d'estime and surprisingly popular when it came out. But after United Artists finessed the figures its makers netted "not one penny". Fortunately, as Brownlow says: "To me film is a religion. I don't expect to get paid to make it, but I do expect total dedication."

In 1968 Brownlow edited Tony Richardson's The Charge of the Light Brigade – "the most enjoyable thing I ever worked on" – but wanted to direct again. After several further commercial projects fell through, the Brownlow-Mollo team started another ambitious shoestring epic, Winstanley. It is "a really English film," Brownlow has said, about the Diggers' valiant, doomed radical Christian commune at St George's Hill, Weybridge, after the civil war. Brownlow's delightful book about the production, Winstanley Warts and All, was published in 2009.

He has worked for television: the Bafta-winning Hollywood (1979) is a definitive survey of the American silent film industry. Numerous other documentaries have followed, including Cinema Europe (1996). The British episode of that series is entitled "Opportunity Lost". "There was a great snobbery about the cinema in this country, which didn't exist in America," he says. "What I found there was tremendous enthusiasm." His experiences of filmmaking in Britain have been too often dismal – with glorious exceptions. But then, he notes, "Somebody said that part of my reaction to British cinema is actually, paradoxically, a patriotic one. I'm so disappointed that we're not better. There's an element of truth in that." - Philip Horne

www.guardian.co.uk/

But while Brownlow's achievements – as a historian of film, in preserving and restoring silent-era classics, and as a director in his own right – have commanded respect, he has never played the career-building game. His Oscar acceptance speech began: "If you ever wondered what reflected glory looks like, this is it!" And it went on to remind the Academy of Hollywood's wretched record, destroying 73% of pre-sound films: "By God, your predecessors did a terrible job of preserving the silent era!" Silent films have always been a cause that needed defending, he told me: "The reason I was doing it was because nobody else was."

So far Brownlow has not been conspicuously honoured in Britain; but then, he has always been rousingly undiplomatic about the shortcomings of the British film industry. This wonderfully English figure – a passionate amateur in the best sense, immensely knowledgeable and wry and idealistic – has often been at loggerheads with this country's movie establishment.

Starting as a teenage silent-cinema enthusiast in the 1950s, Brownlow interviewed a dazzling array of film pioneers. He met and became friends with Abel Gance, director of Napoléon (1927); and also (despite his liberal views) with Leni Riefenstahl. Among the royalty of old Hollywood he met (and in many cases became friendly with) Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, Fay Wray, John Ford, King Vidor, Howard Hawks, Frank Capra, David O Selznick and Fritz Lang. He got to watch Charlie Chaplin directing, despite the strict closed set at Pinewood for The Countess from Hong Kong (1967), because he turned up with Gloria Swanson.

At his school in Crowborough, East Sussex, the headmaster showed silent films on a 9.5mm projector. That inspired him to ask his parents for a 9.5mm projector of his own, and he became a passionate collector. He encountered Gance's Napoléon, which was to change his life, in 1954. "It was to me the first glimpse of what I thought the cinema should be, in which everything looked incredibly real, and yet the camera was doing astonishing things that I'd never seen before, or since."

The excitement of this fragmented two-reel version of Gance's five-hour-plus epic led him, while still at school, to seek out other 9.5mm prints of the film. He found one on a stall in Paris. "My first restoration was on Napoléon, trying to put the French version in with the English version, and it was most unsatisfactory." He has been reconstructing the film ever since, as further footage is unearthed in archives. In 2000 his third major restoration premiered at the Royal Festival Hall to 2,200 people – with a full orchestra and Gance's original triple-screen spectacle. Alas, this sublime five-and-a-half-hour version hasn't been shown since 2004.

When he left school he became a trainee in the Soho cutting rooms of World Wide Pictures. In the business, he heard much talk of the Al Parker actors' agency, and connected it with the actor Albert Parker, villain of Douglas Fairbanks's American Aristocracy (1916). "I rang him up, and said: 'Does the name Fairbanks mean anything to you?' He said: 'Jesus Christ! Doug? I directed him!' And I said: 'What in?' And he said: 'The Black Pirate!' I said: 'I think I've got one of your very early films.' He says: 'Bring it over.' So I took my little hand-cranked projector and I showed it to him on the wall – and he got absolutely fascinated."

While working as an editor he doggedly pursued the surviving silent movie pioneers for interviews, which eventually became the substance of The Parade's Gone By (1968). Two more major studies of silent film followed: The War, the West and the Wilderness (1979) and Behind the Mask of Innocence (1990). He went to the US for the first time in 1964: "To be honest with you, I was chasing a girl. She was an actress who had gone back to New York. So I needed an excuse." While she rehearsed he tracked down silent-film veterans. He flew on to Hollywood and managed to pack in multiple interviews. Josef von Sternberg, he says, was "very, very difficult", even though "I was mad about his silents". Later he met Sternberg's great star, Marlene Dietrich – a contrast to her mentor. "What really amazed me was how warm she was. She pretended she wasn't in silent pictures because it dated her."

Brownlow had made an early start in journalism too, and, even more precociously, by 17 he'd made a first film, The Capture (which doesn't survive), based on Maupassant. In 1956, inspired by hearing a German shout in the streets of Soho, he began making the extraordinary It Happened Here, about a putative German occupation of England in 1940 – starting, cheekily, with a Nazi rally in Trafalgar Square. As it developed, with the help of Mollo as co-director, the film became a corrective to the myths of English wartime exceptionalism: "If the Nazis had come over it would have been just like France and the Netherlands and everywhere else." The finished film, with its painfully believable dark vision, was a succès d'estime and surprisingly popular when it came out. But after United Artists finessed the figures its makers netted "not one penny". Fortunately, as Brownlow says: "To me film is a religion. I don't expect to get paid to make it, but I do expect total dedication."

In 1968 Brownlow edited Tony Richardson's The Charge of the Light Brigade – "the most enjoyable thing I ever worked on" – but wanted to direct again. After several further commercial projects fell through, the Brownlow-Mollo team started another ambitious shoestring epic, Winstanley. It is "a really English film," Brownlow has said, about the Diggers' valiant, doomed radical Christian commune at St George's Hill, Weybridge, after the civil war. Brownlow's delightful book about the production, Winstanley Warts and All, was published in 2009.

He has worked for television: the Bafta-winning Hollywood (1979) is a definitive survey of the American silent film industry. Numerous other documentaries have followed, including Cinema Europe (1996). The British episode of that series is entitled "Opportunity Lost". "There was a great snobbery about the cinema in this country, which didn't exist in America," he says. "What I found there was tremendous enthusiasm." His experiences of filmmaking in Britain have been too often dismal – with glorious exceptions. But then, he notes, "Somebody said that part of my reaction to British cinema is actually, paradoxically, a patriotic one. I'm so disappointed that we're not better. There's an element of truth in that." - Philip Horne

www.guardian.co.uk/

Gerrard Winstanley (19/10/1609- 10/09/1676) Vision Still Burning Bright

http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film2/DVDReviews46/winstanley_blu-ray.htm

Land and Freedom

The Diggers' vision to reclaim the Land - April 1649

The Diggers' vision to reclaim the Land - April 1649

An account from St .George's Hill April 1999

Quotes from Winstanley and other Diggers

Then and Now - 1649 and 1999 - little has changed!!!

Threats against the 1999 Diggers from ?? the rich and powerful ??

The True Levellers' Standard Advanced - The Diggers' Manifesto in full

The Land Is Ours (offsite) facilitated celebrations and events in the UK around the Diggers anniversary - 1st April 1999

1968 - San Francisco digs Gerrard Winstanley (offsite)

More on this page by, about and from The Diggers:

August 1998 - Why celebrate the Diggers?

The 1990's Diggers song: 'The World Turned Upside Down'

Declaration from the Diggers of Wellingborough - from the poor inhabitants of the town

And other Digg-linx

http://www.bilderberg.org/land/diggers.htmIt Happened Here (1966):

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar